Aside from the issue of party leadership that I have written about here, what else can we learn from the Swedish election campaign – for the sake of the future of the Swedish Social Democrats, and for Labour too? Beyond any debate that may arise here, this will be the issue for the second EUROPA-Soirée of the Labour Movement for Europe, taking place on Tuesday 17th October [more info] – all are welcome!

Let’s reflect: what did the Social Democrats do well in their campaign, and what did they do badly? Above all else, the publicity materials and internet campaigns rank as the major campaign successes as far as I am concerned. When it comes to these issues, Labour has a lot to learn.

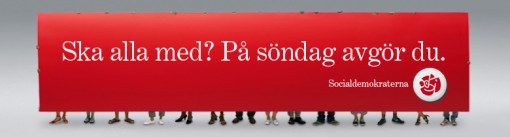

The many election posters across Stockholm looked professional while the slogans were strong and clear. The materials handed out to voters struck a similar note, with happy people holding ‘Alla Ska Med’ signs (means Everyone Is Coming Along). After a shaky start, the main Social Democrat website improved a lot, and hundreds of party branches and activists used S-Info to publicise the campaign.

The jury’s out when it comes to two other major components of the Social Democrats’ efforts: the valstugan and the press and media work during the election. The valstugan (election huts) have long been the bedrock of election campaigning in Sweden; potter along to the hut in your local town centre and have a chat with the local politicians. But do these huts actually change much? They are also very resource-intensive (see below). It also proved consistently hard for the Social Democrats to get their messages across in the press throughout the campaign: an issue of the right-wing press ownership, or a matter of the message?

However, the most serious problem with the whole campaign in my mind was the extremely inefficient use of the massive human and financial resources that the Social Democrats have at their disposal. Leafleting routes were not properly mapped out or effectively manned. There seems to be little logic behind decisions of who to send where to do what campaigning, and little communication with activists about the core messages that needed to be explained to activists. Further, while it might be quite sweet and pleasant, is handing out roses to voters the most effective way to get the message out?

I think the latter issue is in large part due to the problems of a party having been in power for too long; complacency develops as officials stay in their jobs for too long. I’m not sure where door-knocking organised according to a military style plan (as Labour does) would work in Sweden – it does not match the electoral culture – but changes are badly needed, or else the 2010 election might look quite grim too.

There seem to be several factors at work here:

– There’s a long-term decline in the social democratic vote. It is now at its lowest level for more than 80 years. It has been under 40% in all the last three elections (admittedly it was 39.9 last time), whereas it was 42% or higher in 18 of the 19 preceding elections, the exception being relatively recent (1991). One suspects the party has suffered from the increase in the Left vote since the fall of the Berlin wall and from the introduction of the Green Party, but the figures are far from clear. This year’s Left result was no better than 1988’s and only marginally better than 1979-1985. The first three elections which the Green Party contested, including the one where it got more than 5%, showed the SD vote at the same level or higher than in the two elections previous to Green participation.

– Similarly, though, there’s been a decline in the proportion of the left-of-centre vote that goes to the SD. If I correctly understood the detailed breakdown shown on TV last night, young people are less likely than old people to support SD, but they are much more likely than old people to support the Left Party or the Greens.

– More importantly, there’s declining participation in politics, increased political alienation indicated by declining turnouts (80%-81% in the last three elections, versus 85-87% in the three before those, and 88-92% in the 1970s). Also indicated by the increasing number of votes that go to micro-parties and protest parties that fail to cross the 4% threshold. These “others” received 5.7% of the vote this year, which is nearly twice as much as in the previous election, more than twice as much as in 1998, almost six times as much as in 1994 (1%), twelve times as much as in 1985, 30 times as much as in 1982, and 60 times as much as in 1960.

Clearly some sort of disconnect has begun to develop between Socialdemokraterna and their electorate. This is what they need to remedy.