Scotland: Why independence after 300 years?

NOTE: this is a piece commissioned by the Norwegian online magazine Vox Publica, and was translated into Norwegian for that purpose. The Norwegian version can be found here: Skottland: Hvorfor uavhengighet etter 300 år? The English original is here with permission from Vox Pubica, but – unlike other posts on this blog – is not Creative Commons Licensed, and hence my not be syndicated or re-used. The piece gives an overview of the Scottish Independence debate and how Scotland arrived where it is today.

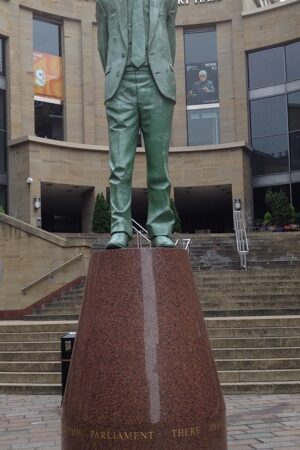

A statue of the first First Minister of Scotland in modern times, Donald Dewar, stands in Glasgow’s Buchanan Street. The stern and bespectacled Dewar cast in bronze gazes down at a political scenario on the streets below that bears little resemblance to the Scotland that gained political powers devolved from Westminster in 1999, following the 1997 referendum to establish the Scottish Parliament in the early years of Blair’s government.

A statue of the first First Minister of Scotland in modern times, Donald Dewar, stands in Glasgow’s Buchanan Street. The stern and bespectacled Dewar cast in bronze gazes down at a political scenario on the streets below that bears little resemblance to the Scotland that gained political powers devolved from Westminster in 1999, following the 1997 referendum to establish the Scottish Parliament in the early years of Blair’s government.

The idea of the Labour Party throughout the 1990s, most strongly promoted by Dewar and former Foreign Minister Robin Cook, was that granting political power to Edinburgh would stop the demands for an independent Scotland that had been steadily growing since an unsuccessful referendum on devolving powers held in 1979. George Robertson even stated that “Devolution will kill Nationalism stone dead”; how wrong he has shown to be.

That the referendum on independence is even happening on 18th September, and that Yes to independence is in with a chance of winning, has depended upon a unique combination of circumstances.

The first factor has been the remarkable rebound of the Scottish National Party (SNP). The SNP struggled at the end of the 1990s and into the early 2000s, as enduring strength of the Labour Party in Scotland, together with the initial popularity of devolution, limited its appeal. Yet the return of Alex Salmond to the leadership of the SNP in 2004, together with his enterprising deputy Nicola Sturgeon, rejuvenated the party’s fortunes. Salmond’s tactical nous and administrative ability have been consistently underestimated by both press and politicians alike in London. Salmond and Sturgeon have managed to fuse traditional, often rural and conservative, support for Scottish nationalism with progressive, modern social democratic voters who have come to view independence for Scotland as the best means to achieve social justice there.

The 1999 devolution arrangement was, as a political calculation, based on the assumption that the political strength of the Labour Party in Scotland would endure and, just in case, a proportional election system has been used in the Scottish Parliament from the start, the idea being to prevent any party being able to govern alone. The decline of Scottish Labour is hence the second factor that brings Scotland to the brink of independence. Labour has never taken the Scottish Parliament seriously, while the SNP has done so, and as Labour’s traditional supporter base among industrial workers has withered so the SNP has gathered support among the non-trade unionised left.

This decline of Labour’s support allowed the SNP to become the largest party and Alex Salmond to become First Minister in 2007, and they repeated this in 2011, achieving an overall majority – something that was supposed to be impossible in the design of the Parliament.

Margaret Thatcher and the Conservatives are still blamed for Scottish industrial decline, so a post-Thatcherite administration under David Cameron in London has rekindled old resentments among the former working classes in Scotland – the third major factor. Meanwhile sluggish economic growth for the last decade, coupled to social security funding restraint imposed by Westminster, has brought younger generations into the independence cause.

The response from London throughout this process has been one where legal barriers have not been placed in the way of possible independence, but the approach from London has been one of disregard bordering on disdain for Scotland, and an underestimation of the SNP and Salmond. The referendum question – a simple Yes or No to independence was a direct result of this. David Cameron, looking at opinion polls that were set against independence at the time, chose the tactical option – to offer Salmond the referendum the SNP’s manifesto had demanded, but to insist that so-called “DevoMax” (a maximum amount of powers to be devolved from Westminster to Scotland) would not appear among the choices on offer to the Scots. Now, as the polls have narrowed (with some even showing Yes in the lead), leaders of the UK’s main political parties have been scrambling to promise extra powers to Scotland, even though postal voting in the referendum has already opened.

While all of these factors set the context, they nevertheless do not encompass the issues that are at the heart of the referendum campaign. Why might the Scots actually consider breaking up a union that has lasted since 1707?

A series of political and economic arguments have been deployed by the umbrella campaign groups on both sides. Yes Scotland, fronted by Alex Salmond, has focussed mainly on the political case for independence – that Scots deserve better government, and that they been saddled with Conservative governments in Westminster but a majority of Scots has never backed the Conservatives. The picture Salmond paints is of a pro-politics, civic independence, where an independent Scotland would be a more just and fairer country than currently. Allowing 16 and 17 year olds, and EU citizens resident in Scotland, to vote, plus the addition of groups like Polish Scots for Yes and the Scottish Green Party to the Yes campaign give the campaign a positive, modern, leftish-leaning, feeling. The Yes side has most definitely risen above narrow definitions of nationalism or separatism.

A series of political and economic arguments have been deployed by the umbrella campaign groups on both sides. Yes Scotland, fronted by Alex Salmond, has focussed mainly on the political case for independence – that Scots deserve better government, and that they been saddled with Conservative governments in Westminster but a majority of Scots has never backed the Conservatives. The picture Salmond paints is of a pro-politics, civic independence, where an independent Scotland would be a more just and fairer country than currently. Allowing 16 and 17 year olds, and EU citizens resident in Scotland, to vote, plus the addition of groups like Polish Scots for Yes and the Scottish Green Party to the Yes campaign give the campaign a positive, modern, leftish-leaning, feeling. The Yes side has most definitely risen above narrow definitions of nationalism or separatism.

Better Together – the official title for the No campaign – has been fronted by Alistair Darling, Labour Chancellor in Gordon Brown’s government during the financial crisis. The arguments deployed by Better Together have been more economic and more negative than those of the Yes side, prompting Yes to brand Better Together “Project Fear”. Darling has relentlessly pressed Salmond on the SNP’s plans for an independent Scotland to continue to use Sterling (Darling claims London could refuse this, yet Salmond refutes this), and the essential case would be that an independent Scotland would be poorer than it would be if it remained in the Union. Better Together has often looked like an uneasy alliance of the three main Westminster parties, with Labour leading the rhetoric with Cameron’s Conservatives and Clegg’s Liberal Democrats sheepishly following. That the UK Independence Party (UKIP) is on the No side has been used by the SNP to its advantage. Interestingly the role of the United Kingdom’s North Sea oil has not been central to the campaign on either side; some of the oil fields would remain in the hands of the rest of the UK, and some in Scottish hands, and in any case production from these fields is decreasing.

Scotland’s international role has been fought over by both sides, yet with no decisive win for either. Salmond wants to rid Scotland of the nuclear weapons based at HMNB Clyde to the west of Glasgow but no solution to move the base has been found, and the SNP’s plan to join NATO could be called into question as a result of this issue. Scotland’s membership of the European Union has also been fiercely debated, with the No campaign and some Brussels politicians stating that Scotland would have to apply like any other state. The SNP argues that Scots are already EU citizens, and that this cannot be removed from them, and hence Scotland would remain part of the European Union. The EU is important to the Yes campaign, in that EU membership makes the prospect of an independent Scotland less scary. The result on 18th September will also have profound implications for Catalonia, and possibly for Belgium and minority populations in the Baltic States and Romania, although so far only the Scots have found a way to organise a legal referendum.

With less than a fortnight to go, and with the polls showing both sides neck and neck, this campaign will go to the wire, and Scottish politics will be changed for the foreseeable future whatever the result. The referendum has prompted record levels of people to sign onto the electoral roll and turnout is expected to be above 80% – 15% higher than any election in the UK since 1997. This referendum, and the debate it has provoked, has been an extraordinary political event. Politics is alive again in the British Isles, but how united will the islands be after 18th September?

Looking at this debate from the outside, I sometimes had the feeling that the “no campaign” was its own worst enemy. They largely restricted themselves to denigrating the other side. What they should have done, instead, is indead pointing out a “better together”, a vision on how the “together” could be improved.

Of course, given the pro-EU attitude of Scotland, that’s not that easy since one of the aspects of the present constellation is that Scotland could possibly be dragged kicking and screaming out of the EU by Westminster, whereas it would be suicidal for Cameron to give a guarantee that the UK would not leave the EU…

In any case, a more fitting title for the “no campaign” would have been “worse apart” rather than “better together”. They’ve been restricting themselves to claiming that the situation in Scotland would be deteriorating after a split rather than bringing up a positive vision of their own. And given the fact that at least for some people in Scotland, the notion of something worse than the status quo is barely conceivable, simply due to different value sets, it was myopic to believe that such a strategy would be successful.

The problem is, of course, that now the two sides are so close that no poll will actually give closure.