The Martin Schulz bounce

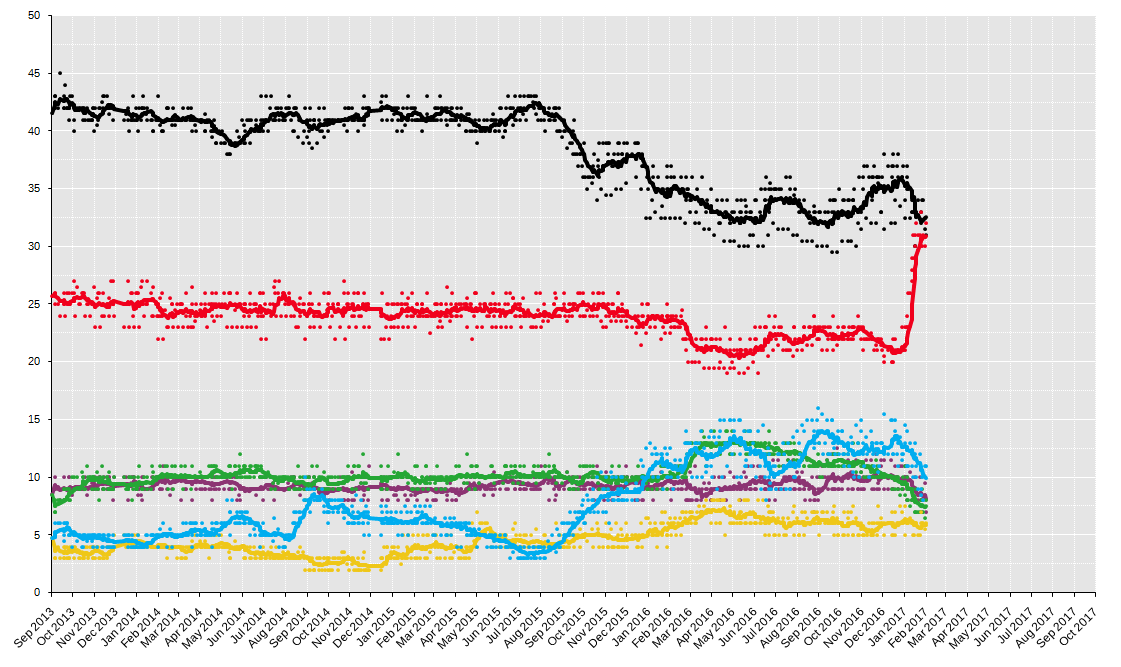

What is going on in German politics, just 7 months ahead of the 24th September Bundestag election? How can a party, the SPD – that was consistently 10 points behind the CDU in the polls – suddenly be running neck and neck with Angela Merkel’s party? This graph from Wikipedia maps the state of the polls:

The sharp upturn in support for the SPD of course comes after it was announced on 24th January that Sigmar Gabriel, the SPD’s long-term leader, would not run as the party’s Spitzenkandidat in the September election, and that Martin Schulz should run instead. But what is going on here, and what is actually due to Schulz and what is due to other factors in German politics?

The most obvious point – and one that, for example, yesterday’s New Statesman’s piece about Schulz fails to adequately cover – is simply that Schulz is not Sigmar Gabriel. The Martin Schulz bounce could at least in large part be seen as an anti-Gabriel bounce. Since the formation of the Grand Coalition after the 2013 Bundestagswahl, Gabriel struggled to breathe any life into the SPD (despite some of the most major successes of the government being due to the SPD – the minimum wage for example), and the party slipped further in 2015 and 2016 in part due to the rise of the populist AfD. Worries about the SPD’s predicament under Gabriel had been around for years, but it was assumed that the party would sooner see Gabriel run in 2017, and then rebuild, rather than pass the mantle to someone else.

The SPD had two other viable alternatives to Gabriel – Hannelore Kraft in Nordrhein-Westfalen, and Olaf Scholz in Hamburg – but neither was willing to take the risk and step up to the federal level and challenge Merkel. Both had too much to lose at the Land level. That was not the case for Schulz – his term as President of the European Parliament was anyway over, so he had nothing to lose by stepping across to German politics. Also remarkable for a politician previously only active at EU level, Schulz was already reasonably well known in German politics (indeed Kraft was the only SPD person better placed than him in a December 2016 poll) – this is not some sort of faceless, unknown Eurocrat.

While Schulz might look like a typically grey and dull politician, there is enough about him to allow him to seem a little different in German politics. His well documented difficult early life and battle with alcoholism, and leaving school without an Abitur, is in stark contrast to the heavily intellectual German political elite. The language he uses in his television appearances sounds more normal, more down to earth, than many of his counterparts. Meanwhile his European experience and multilingualism means he looks like less of an inward looking old-style social democrat than Gabriel. Lastly he is the first SPD candidate for high office not tainted by association by Gerhard Schröder’s government of the late 1990s – Gabriel, and Steinbrück before him never managed to move on from the association with Schröder’s controversial Hartz IV reforms. No-one can connect Schulz with that.

Having observed Schulz in Brussels for a lot of the last decade, I do wonder whether this ‘bounce’ that the SPD has enjoyed will really hold through until September. Schulz can be blunt and tetchy and come across as rather bullying in his style. He has never been subjected to the sort of scrutiny in the European Parliament that he will receive in a Bundestagswahl campaign. He is also a cunning, power-playing politician, ready to strike a deal in his interests – and this can sometimes come across negatively.

So that is the SPD side. But what about the rest of the political field? The new support for the SPD has to come from somewhere after all.

While she is feted abroad as a symbol of European and German stability, all is not altogether rosy for Merkel in the CDU. The party was willing to tolerate her centrist pragmatism so long as it worked electorally, but as the CDU’s support in the opinion polls began to drop from 2015 onwards, so rumblings about whether she is really the right person to continue to lead the CDU have become more marked. The party’s congress in December 2016 revealed some of these fault lines. The relationship between Merkel’s CDU and the Bavarian sister party frayed markedly during the refugee crisis, and while efforts have been made to patch things up since, the CDU and CSU do not approach the election in an entirely harmonious manner. The SPD looks rather united in comparison.

It is not only from the CDU that the SPD has gained. Both the Grüne and Die Linke are down in the polls. The Grüne have struggled to define themselves, and an obvious pro-European like Schulz poses a problem for them – Schulz is more appealing to urban, university-educated lefties than Gabriel was, and that is the typical base of green support. Schulz, with his rhetoric about equality and fairness sounds, in his words at least, more like a proper social democrat, and so he marginalises Die Linke. Meanwhile Wagenknecht, the co-leading candidate of Die Linke, remains a controversial character – Schulz seems sensible in comparison. Even the populist AfD has not been immune to the effect of Schulz – blue collar workers who have seen the populists as an alternative to the political mainstream have begun to return to the social democrat fold, while internal division and critique of party leader Petry have dented the AfD’s effectiveness.

All of this also needs to be borne in mind when it comes to thinking about coalitions after the election. Were Schulz and the SPD to be narrowly ahead of the CDU-CSU, a grand coalition (yet with the roles reversed) would be the most likely option. Again having seen Schulz in Brussels, and his work with the Christian Democrat Jean Claude Juncker, such a coalition would likely be Schulz’s favoured route. Even if SPD-Grüne-Die Linke (the so called R2G coalition) had enough seats for a majority, I am not at all convinced that Schulz would want to team up with Wagenknecht.

So – to conclude – Schulz as the SPD’s Spitzenkandidat has suddenly made the Bundestagswahl more exciting. But his bounce is at least as much to do with Schulz not being Gabriel as anything that Schulz himself brings. Plus the issues all other parties face have also contributed to the SPD’s partial recovery. Will all this hold throughout the campaign? There I am rather sceptical – time will tell.