Teaching EU online communication through simulation – the twitcol case

For the first time in the academic year 2015-16 I am a member of the faculty of the politics department at the College of Europe in Bruges. My own MA is from the College of Europe (in 2003-04) and it is good to be back there as a teacher this time. The College operates a system of a kind of flying faculty – we are called upon to run courses or seminars, but are not actually based in Bruges. My own course is a short, optional one entitled Online Communications in EU policymaking, but this post concerns my contribution to a compulsory course for all 96 politics MA students run by Pierpaolo Settembri and Costanza Hermanin – the EU legislation simulation game.

The basic idea of the simulation game is relatively well known – each student gets allocated a role, and all of the aspects of an EU legislative negotiation are played out by the students playing these roles. Pierpaolo is the author of a book about how to use these sorts of games to teach about the EU.

This year’s game at the College featured two innovations. The first was the presence of non-legislative actors in the game (campaigners, lobbyists and press), and tools to allow delegations to communicate online with each other during the game. The topic this year was conflict minerals and their import (or not) into the EU, although the lessons here would work for more or less any legislative issue.

Does a simulation game need its own technology?

While the importance of online communication (and especially Twitter) is by now well known and accepted in EU circles, the first question Pierpaolo and I had to answer was whether we should just use public tools (Twitter itself, possibly with locked accounts?), or develop our own tools for the simulation? We went for the latter option for three reasons. Firstly, public accounts on Twitter are exactly that – public – and this is a simulation game (i.e. not real life), and we did not want to deluge the rest of Twitter with tweets. Meanwhile locked accounts prevent the use of some aspects of Twitter (retweets for example). Second, running our own tools meant we have complete control of the data – and hence statistical analysis of that for the assessment of the students. Third, it is possible to erase all traces of the game afterwards – we do not want what students did hanging around on the internet. This also meant students had the safety to be able to get things wrong, learn, and try again.

Choice of technology: GNU Social (complemented with WordPress)

Having opted for our own system, the question was: what tool would do the job? Also aware that we had zero tech budget! GNU Social (previously known as Status.Net) is an open source tool that was close enough to Twitter to be useable. A profile was made for every student on our GNU Social installation (that we called twitcol) before the start of the game. In addition an installation of WordPress with multi-user functions enabled was used for longer form or blog style pieces – here students could choose to make a site if they wished, and 21 opted to use this additional tool (we called that wpcol). This was password protected.

Hosting, installation and databases

Both GNU Social and WordPress are PHP/MySQL based tools. This means they will run on more or less any web server – starting from cheap shared hosting packages that cost a couple of Euro a month. While WordPress is simple to install and get running (some web hosts even offer one-click installs), GNU Social is a bit of a mess. It needs at least PHP version 5.5, and some relatively unusual PHP extensions, to get it to run – you may need to contact a web host to get help with these. Also note that while you can install and use WordPress without going anywhere near the MySQL database where it stores its data, that is not the case with GNU Social – I was using phpMyAdmin to manually edit database fields very regularly. Sometimes this was to save time (creating usernames), sometimes to fix bugs, and at the end to export statistical data from the system. Unless you have someone who has the skills to do this I would not attempt to do this exercise with GNU social!

The installation of GNU Social was relatively standard – we used the Neo Quitter theme to make it look as much like Twitter as possible, and imposed a 140 character limit in the settings. Note however that GNU Social is not really adapted for mobile devices – on the web in any case. The Bit.ly plugin was used to track links clicked, and the Social Analytics plugin provided some statistical data. Privacy settings were locked down to make sure no tweets could be read by anyone other than registered users. However despite our best efforts there are a few bugs with GNU Social that I simply couldn’t solve. Sometimes deleting tweets would cause tweets posted before it to not appear in the timeline (although those tweets remained on users’ profiles), sometimes the character counter refused to work, and if an image upload failed it caused an issue with the nesting of tweets. Also – by default – GNU Social sends masses of e-mail notifications, and this was sufficient to prompt my website host to think the students were spammers and the hosting account was temporarily suspended! I had to keep an eye on the installations throughout the game (that lasts 3 weeks), answering queries and bug reports from the students.

So did it work?

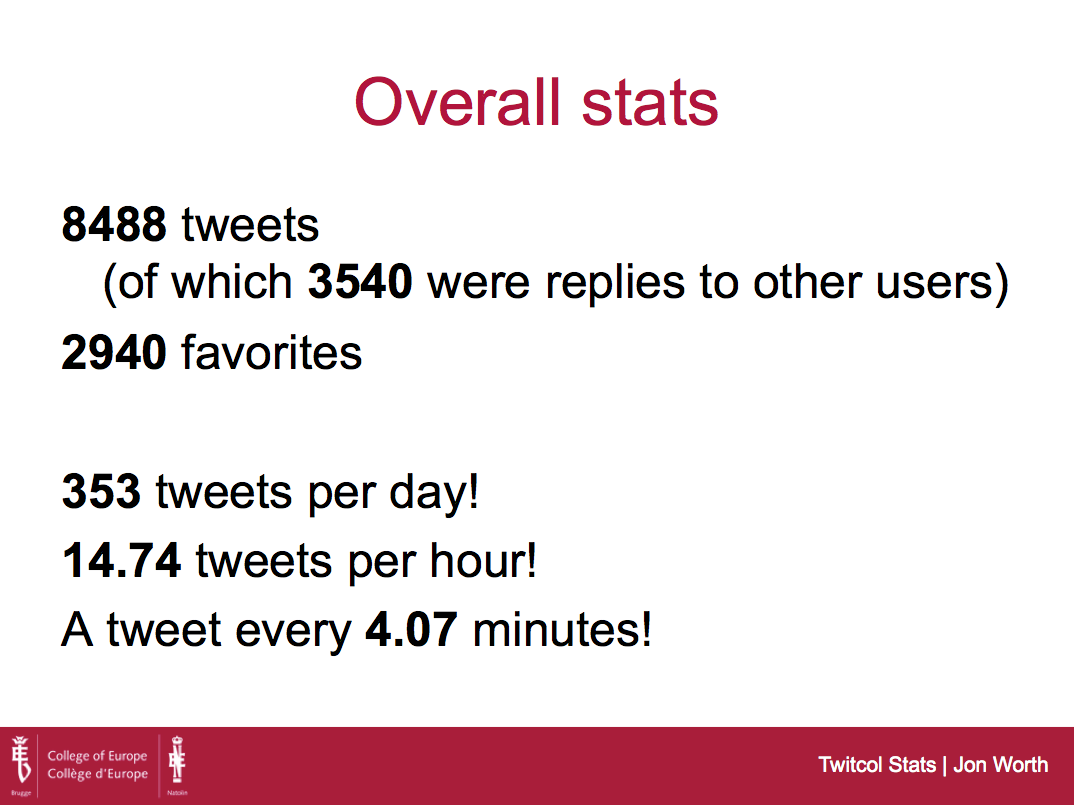

Absolutely! And beyond our expectations! More than 8000 tweets were written by the 96 students throughout the 3 weeks of the exercise. twitcol was central to the game, as it is central in Brussels.

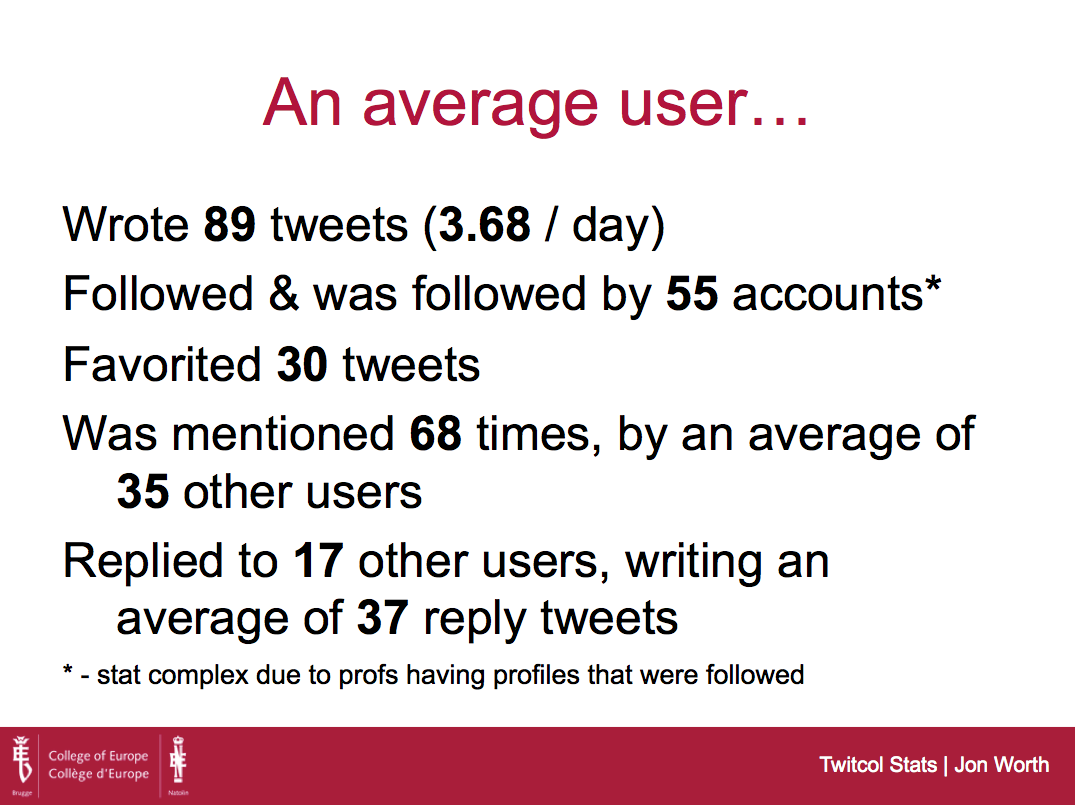

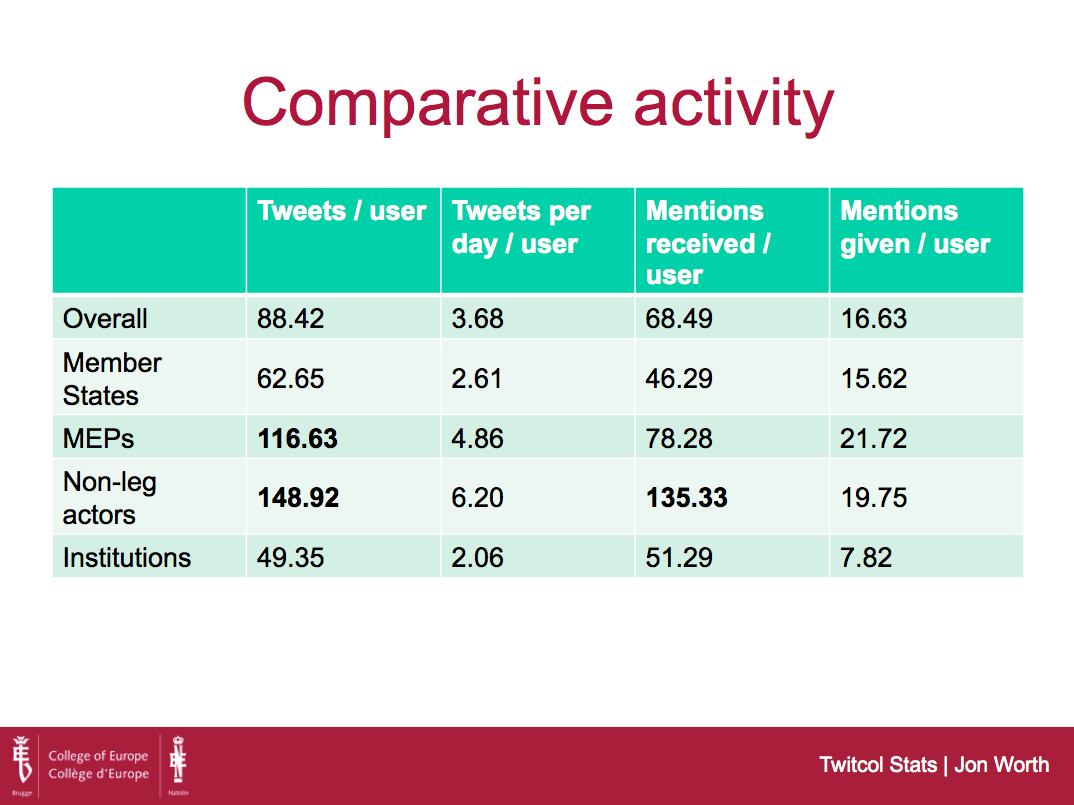

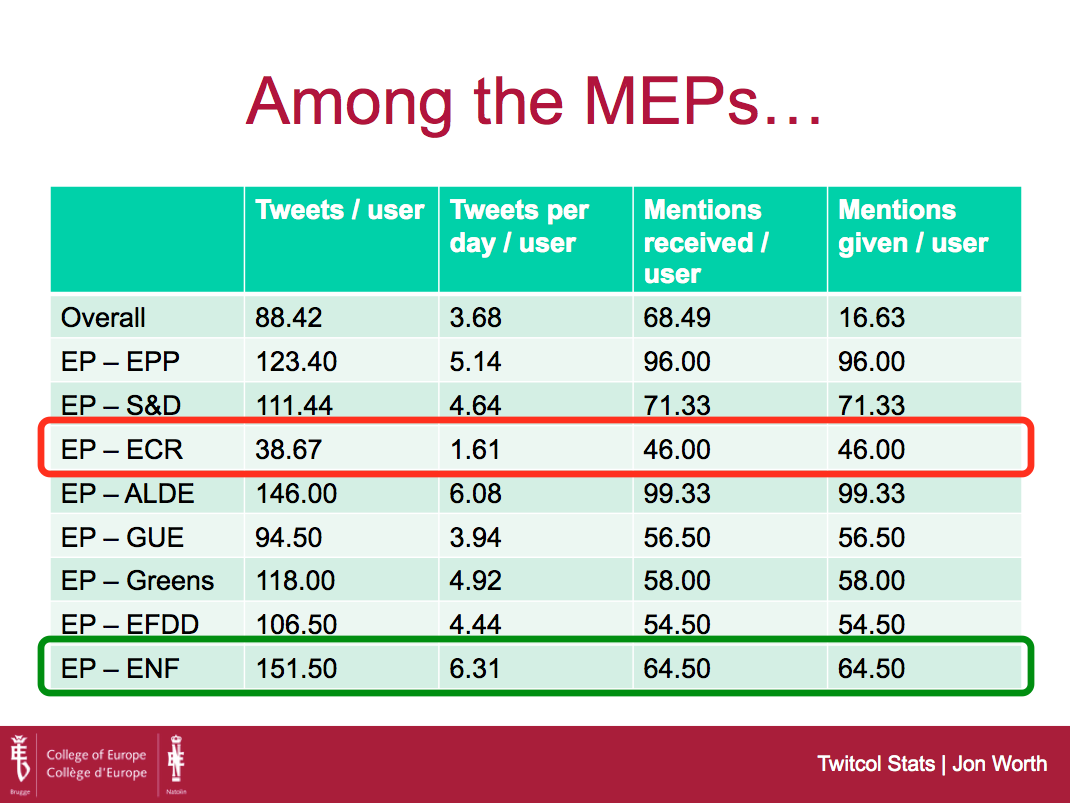

These screenshots are from the presentation of the end results of the game:

More detailed stats are not presented here to preserve the anonymity of the students, but essentially the outcome actually was reasonably realistic – with non-state actors (and especially journalists) using twitcol more actively than those with formal legislative power. Furthermore, MEPs made more use of the tool than either the Member States or the Commission. Content outside twitcol written by the journalist players gathered more clicks than content written by other players. Tweets ranged from the critical to the serious, from news breaking to dull – just like the regular EU twittersphere.

The stats above were gathered from the Social Analytics plugin in GNU Social that I had to hack a bit to get it to do what I wanted, and then an export of MySQL database data as a CSV file then analysed and sorted in Excel. All the stats gathering took about 4 hours to do, and each student was given a PDF document with the breakdown of her/his own statistics.

Conclusion

This was a tremendous experiment. We had no idea whether it would really work. The technology was a bit flaky, but essentially held together. There are things – not least the statistical analysis and making the thing more mobile friendly – that we will have to improve the next time we run it. But just as it’s now impossible to imagine the EU institutions without Twitter, so too no serious and complex simulation of EU negotiations ought to run without its own equivalent of twitcol. If you have questions about what we did, how, or why, then do drop me a line!

Jon, one interesting comment we received from students is that the missed from Twitcol the “general public”, meaning that it was only open to them and there was no public out there to exercise any form of scrutiny. One idea they came up with to remedy this drawback was to assign a generic Twitcol account to all College students in addition to the normal role-accounts for the POL ones, so that others – not directly involved in the game – could somehow put pressure on the rest. Thoughts?