What would leaving the EU actually mean in practice?

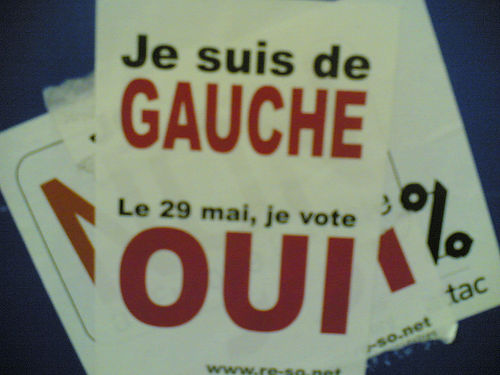

In 2005 I went to France to campaign in the referendum on the European Constitution, making the case for oui. One thing about that campaign has been with me ever since: it was clear what oui would mean (France would ratify) while it was never clear what non would mean. The diverse interpretations of non – from ‘stick with the Treaty of Nice’ via ‘we want a Social Europe instead’ to ‘we want to punish the government’ – meant that non was a responsibility-free shot at the establishment. The EU could have operated with the old treaties, so it’s not as if the non had a particularly high price.

Fast forward 6 years, and calls on left and right of UK politics are growing to hold a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU – in or out. I’ve previously argued why Labour should not favour such a referendum and Nosemonkey has taken apart the People’s Pledge arguments.

This post raises a further issue that all ‘we want to leave’ advocates need to answer: what would leaving the EU actually mean? It’s not as simple as it sounds.

It strikes me that the yes answer to a question such as “Should the United Kingdom should remain a Member State of the European Union?” is simple enough – the relationship with the EU remains unchanged, and the UK fights its corner in the EU, winning some fights and losing some, just as it has since 1973.

But what would about no?

I pose this question with complete honesty – I really do not know the exact answer, and would like to hear opinions on this. Because without a definitive answer to this question, how could anyone realistically make up their mind in a referendum? Leaving the answer to this important issue until after a referendum would be irresponsible in the extreme, because even those arguing for withdrawal contend that the UK’s relationship with the EU is an matter of high importance.

Here – in rough terms – are three possible scenarios for how life could be for the UK outside, making the UK’s relationship with the EU similar to that of Norway, Switzerland or the USA, and I would be keen to hear thoughts on these.

If the UK were to have a relationship with the EU similar to Norway’s relationship today (in the EEA), this might be how it could look. The UK would be legally obliged to implement all aspects of EU law as applied to the Single Market, but not to agriculture and fisheries. The UK would have no say over those Single Market laws and would just be expected to implement them. The UK would contribute much less to the EU budget (Norway participates in some EU programmes, so pays a little) as it would not be part of the Common Agricultural Policy, but UK farmers would not receive CAP cash. This however would mean that tariffs would apply to export of UK agricultural goods to the EU. The UK would lose any say over EU foreign policy, and would receive no regional funds.

The Switzerland case (EFTA membership) is similar. Here the UK would not be legally obliged to apply EU law relating to the Single Market, and yet would – as in the Norway case – have tariff free access to the Single Market for everything except agriculture and fisheries. However the UK would be allowed to develop legislation applying to market issues that would be different to EU law (lower recycling standards for goods, or lower sanitary standards for foodstuffs for example). This could be argued to be an extension of democratic control in comparison to the Norway case, but would create non-tariff barriers to trade – manufacturers would have to make different versions of goods for the UK market and the EU market. It is worth noting that Switzerland implements all EU food law precisely to avoid this sort of thing. Agriculture and fisheries, and foreign policy and regional funds would be the same as the Norway case.

The USA case is the most extreme. Here the UK’s trade relationship with the EU would be regulated by international negotiations in the WTO, meaning that – within reason – the EU could impose tariffs on the export of goods and services from the UK to the EU, and the UK impose tariffs in return. Any market standards would be free to develop any way the UK government saw fit, but each development at odds with the EU Single Market would create non-tariff barriers. Importantly in such a case the automatic right of UK citizens to live and work in the EU, and EU citizens to live and work in the UK, would not be guaranteed. Agriculture and fisheries, and foreign policy and regional funds would be the same as the Norway case.

In short the Norway case would cause least disruption to trade, but is questionable in democratic terms – with no seat at the negotiation table in Brussels and a legal obligation to implement EU law this solution is even less democratic than current arrangements. The USA case is the opposite – a win for democracy, but a hit for the economy. The Switzerland case is a bit of both.

Which of these scenarios do those that advocate the UK leaving the EU actually want?

May 15, 2005 via Flickr, Creative Commons Attribution

What was the author’s position in the 2005 referendum on the European Constitution in France?

Jon, You are doing what europhiles always do in debates like this. You try to present a false question and a false dichotomy to the public buttered with a thick spread of fear, uncertainty and doubt. This of course is what won the 1975 referendum and we are seeing it with the Scottish independence referendum campaign.

The consequences of out will only become clear post referendum as the nitty gritty of our future relations with the rump EU will have to be negotiated. The only certainty is that the rump EU would be acting against its own interests by putting up trade barriers. Staying in will have unknown consequences too as evidenced by the 1975 referendum yet no europhile will give us a 1000 page report on what happens if we stay in.

UK based companies would have to follow rump EU market rules when exporting that is true but anyone who exports anywhere has to follow the rules of the local market. We manage to export to Japan without a problem despite not having a seat at the table. The EEA evidently works just fine for Norway and the bilateral model just fine for the Swiss and no model just fine for the Yanks.

For me the convincing arguments for withdrawal are freeing ourselves from the madness of the CAP and CFP, A freer hand in global trade by being outside the Common Commercial Policy, A freer hand in foreign policy by being outside the CFSP although we remain chained to NATO, Small businesses relieved of red tape, ending the encroachment of civil law and the undermining of civil,liberties. Removal of the really really annoying stuff like the burgundy passport, pink drivers licence, blue flag etc.

The government is very keen to trot out the fact that the UK is now a net exporter of cars for the first time in 40 years. This is a result of a policy of attracting foreign multinationals to base their EU wide plans in the UK not for global policy. Leaving the EU is an economic disaster that has little base in empirical gain but emotional nostalgia.

I’d go with the US model if we have tariffs as we run a massive net deficit with the EU it would benefit us a lot more it would also benefit us with the sales of cars as we import more from the EU than we export. We also have the amusing prospect of the EU imposing tariffs against Rolls Royce engines used to get Airbus planes into the air, not to mention the wings that are vital to most planes otherwise they would be making a rocket although without a propulsion mechanism it probably wouldnt even be that. Food is cheaper & of better quality from places like New Zealand, Canada & Australia which are all countries we can negotiate our own free trade agreements with & as we share security & Language & many laws with these countries I don’t see any issues to a sustainable working relationship

@Jon it’s absolutely true, as you say, that *if* the UK wanted a relationship like Norway’s then “the UK would be [obliged to implement Single Market laws]”.

But @Richard ‘s statement, taken by itself, is still true.

If the UK wanted a relationship to the EU like America’s, or Japan’s or Australia’s, then it wouldn’t have to implement these laws. Can you not admit this?

Indeed. But the phrase in the original blog entry related to Norway.

@Richard – if the UK wanted a relationship like Norway’s then “The UK would be legally obliged to implement all aspects of EU law as applied to the Single Market, but not to agriculture and fisheries” is absolutely true. Norway is in the EEA.

Now if the UK were to try to get some arrangement where it negotiated bilaterally then that would not be the case – i.e. like Switzerland. Which was precisely the point of this blog entry – to make it clear what the options are.

In short: being like Norway is only a fake sort of independence.

“The UK would be legally obliged to implement all aspects of EU law as applied to the Single Market, but not to agriculture and fisheries.”

Simply not true.

“Let the UK and its true Euro-allies find themselves and work together to become prosperous and free of Germanic control” – but most Britons are off Germanic descent! Anglo-Saxons!

It’s better for the UK to teach their children German or a Germanic language. Forget French or any other latin language. They are more lazy and not so hard working.

How about this… Sweden AND the UK leave the EU. We both form a second union involving Sweden, The UK, Sealand, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Iceland and a liberated Greenland. Our regulations are much more geared towards sea trade, fishing and banking. Why isn’t this on the cards, people? Traditionally, the UK has MUCH stronger relations with Scandinavia than places like France, and the Swiss affinity towards banking is also something the UK shares. I am from the UK and I don’t much like the amount of power Germany has over the EU. They are in charge (not that they haven’t earned it. The Germans have worked hard), but the question is, Europe is divided between the banking and fishing countries and the tech and manufacturing countries and how can everyone get what they want. A single union cannot cater to all of us. Let the UK and its true Euro-allies find themselves and work together to become prosperous and free of Germanic control.

We have a a £43 billion trading deficit with the EU, meaning we buy £43bn worth of goods more from them than they buy from us. So there is no way on earth they would start putting up trade barriers with us. We are also the only nuclear power in the EU other than France and London is the financial centre of Europe, so we would still have influence, if not officially. I would love a think tank to do a proper analysis of the likely impacts on business/trade of leaving the EU.

Also, don’t forget we’ll have the Hope and Change cards to play!

What do we want? Freedom!

Jon,

the question seems to suggest that pro-sovereignty people are one homogeneous group, which of course they’ve never been. When there was a referendum back in 1975, the two most prominent politicians on the pro-sovereignty side were Enoch Powell and Tony Benn, who were quite opposite in most of their other opinions.

The lack of coherence that you are drawing attention to is mainly due to the fact that a referendum is not on the agenda. The political establishment is dead against it, even though the ‘stay in’ side would have a very good chance of winning and killing the issue, especially as that side would be far more organised.

Speaking personally, if we left, I would expect the UK to agree some kind of deal with the EU, in the same way as many countries do, whether they’re in Europe like Switzerland or far away, but I see no purpose in working out the nitty gritty when it’s still only a pipe-dream. Besides, if a referendum does take place, such arguments will not carry the day, and the most persuasive arguments for leaving will be based around emotive issues like national sovereignty and self-determination, the democratic deficit and the corruption of the Brussels elite. The idea of someone writing a 1000-page document is ludicrous. If somebody did do this, why would I, as an individual with my own opinions, be bound to somebody else’s view of the issue? What I would be doing is hammering away at the European Arrest Warrant and things like that, not setting out concise plans. I would expect a very dirty fight from the EU side, and would aim to match it blow for blow.

Finally, I just want my country out of the EU, and I’m happy to leave everything else until that has been achieved. If we were to leave, it would change the whole game, in terms of the balance of power between, say, Norway and Switzerland on one side and the EU on the other. Maybe the UK would get together with such countries, and thus be able to thumb the nose at Brussels to a greater extent. Maybe also, countries like Poland or the Czech Republic would seek to follow us out of the EU.

I hope this helps 🙂

@Jon — you can change the EU from within, whilst heading for the exit. I support making the EU more accountable and democratic, and also withdrawal from the EU.

Second lot of replies… last comment got too long!

@Martin – interesting thoughts. As you’re surely well aware by now (as a previous commenter here!) I disagree with you on one issue – that it’s better to try to change the EU from within it, rather than jumping out. But your concerns about the Euro and the way the EU is currently developing I broadly agree with. I also share your concerns about referendums. As for the 1000 page document – you could bet that if a referendum were to be held the European Commission would be called upon to produce something, which would then simply be attacked by the No side… which brings us back to the essence of the question I pose in this blog entry – what do withdrawal from the EU people actually want? And how would that work?

@Justin – there are some very good young, determined MEPs in Netherlands and Sweden. Marietje Schaake and Åsa Westlund for example.

OK then folks, here are some replies… My apologies that this has taken so long.

@AJ (second comment) – I disagree that the EU resembles some sort of federal state. It’s lacking two basic components to justify that term – a proper federal budget, and democratic institutions. Plus its competence in the areas that you mention are exercised together with the Member States.

I agree that on the Scotland case there would have to be negotiations, and the same with the EU case as well, but there would need to be a case made on the no side for what is actually *wanted*. I still have no proper answer to that, and it’s the main question posed by this blog post. What’s the aspiration for those advocating the UK leaves?

@Kevin – This is not a blog post to go after anyone. I want answers to a substantive question. My most major concern is that too many people in Labour seem to be talking about an in-or-out of the EU referendum, and without some sense to that discussion I think it’s dangerous.

@YankeeGirl – yes, your comment is fair, but it in no way contradicts what I wrote – the UK would lose scope to influence CFSP if it took the Norwegian model, but could indeed align itself with the EU on CFSP matters.

@Norwegian Guy – I think your comment very much proves my point. The Data Retention Directive shows the idiocy of the Norwegian position. Bad legislation that Norway could not influence until it was too late, and putting the Labour Party of Stoltenberg in an impossible position – piss off the EU and endanger Norway’s IT sector that trades with the EU, or piss off his party and a bunch of his voters. The postal services directive will be the same.

On tariffs – just wait for the beef farmers to kick up a fuss! It might not be economically so vital, but politically it could be a real headache.

On foreign policy – question of priorities. Norway has splendid independence, but precious little influence. UK would have some say in world affairs, but less than it does working within the EU towards common goals. But I think we have to agree to disagree on that one.

If only there was an intelligent, young, British, pro-European who could become an MEP and put these arguments forward in the UK media…

Quick reply – I am in rural Denmark for the next few days with very little net access. I’ll reply to all of these points when I get a moment.

To clarify what I meant by staying in the EU being an unknown:

The EU is becoming unstable: the failure of the Euro is undeservedly going to discredit the EU more generally, as will failures over immigration. This is for reasons similar to Dani Rodrik’s trilemma of the world economy: you can have only two of democracy, national sovereignty and economic integration (though as it happens, I disagree with him).

The EU has no mechanism to prevent it from acquiring ever-increasing competences, nor any mechanism for subjecting these to democratic control. It follows that it is stuck on a collision course with the right of people to control their own lives, so opposition to it will increase.

The question is whether an orderly subjection of the EU to democratic discipline and the rule of law is still possible, or whether it will break apart chaotically and peacefully like the Soviet Union. We have a situation where 27 national elites hold vetos on all sorts of matters, which in a real crisis will prove as paralytic as the old Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth system of giving every single aristocrat a veto on everything.

As a proportion of world trade, the EU is declining, so the incentives to get outside the tariff wall and trade freely with the rest of the world will only increase. If the UK were to leave, it would be doing so at a time when other member states would also be considering their options. There may well be a widespread acceptance that the current arrangements haven’t worked, and a willingness to be much more flexible with member states fed up with full EU membership.

I’d be unsurprised if Germany didn’t just lose patience with the EU one day and abruptly quit, whilst the Brits were still trying to fudge an evolutionary compromise on their way away from the centre of the EU.

Leaving the EU and staying in are both unknowns. By default, leaving the EU means staying in the EEA, EFTA, ECHR and WTO and in NATO so the UK would continue to be bound by the associated rules. Supporters of EU withdrawal will be able to conflate the benefits of EU withdrawal with the benefits of withdrawal from EEA, EFTA, and, sadly, ECHR, unless there’s a particularly long lead-up to the referendum.

I count myself as someone who thinks the UK should withdraw from the EU, and indeed that the EU should be abolished, but simultaneously as someone who supports making the EU more democratic, even if that makes it harder to withdraw. The EU withdrawalists owe it to the public to produce the 1000 page document setting out the cost-benefit analysis of withdrawal, but this is very expensive. It’s not as though EU conservatives (that is, those who want to remain members) have produced a comprehensive analysis of the benefits of the status quo, however, so there is fault on both sides.

We will end up with a snap referendum, like the AV referendum, where the racist lies on both sides are repeated for a few short weeks and then the public votes on an undebated proposition. Imagine what it’s like, coming from a country which uses AV, and being told you’re not a democracy.

Jon, you are right to question whether a referendum is the right mechanism. In countries with sensible constitutions (that is, Ireland, Australia, Japan and a few others), constitutional change can only be effected by referendums, so the public are accustomed to being consulted on constitutional matters, and can rest secure that their country’s constitution cannot be subverted by a temporary majority among politicians. In the UK, however, the tradition is to effect changes to the constitutional relationship with external powers such as the EU by stealth or deceit: there was no election or referendum about joining the EU (unlike in newer member states), there was one referendum about the terms of membership, and no further consultation about constitutional changes effected by treaty or judicial malpractice. On the contrary, Brown ratified the Lisbon Treaty having falsely promised a referendum on its predecessor treaty.

If it’s Ok to lie to the public about whether they’ll get a referendum on constitutional changes, and Ok to join the EEC without an election or referendum, it’s Ok to just withdraw without a referendum either. It’s not like anyone would believe David Cameron’s promise of a referendum anymore anyway.

I’m sure that some of the Europhiles were delighted by the farce of the AV referendum, as it will have discredited referendums in general.

The benefit of doing things by referendum is that it counteracts the ability of the business lobby to capture the political parties to prevent the withdrawal decision being taken.

“If the UK were to have a relationship with the EU similar to Norway’s relationship today (in the EEA), this might be how it could look. The UK would be legally obliged to implement all aspects of EU law as applied to the Single Market, but not to agriculture and fisheries. The UK would have no say over those Single Market laws and would just be expected to implement them.”

EEA-countries can veto directives from the EU, if they like. This hasn’t happened yet, but the data retention directive only narrowly passed the Norwegian parliament, and there is, after the recent Labour National Convention, a majority against the postal directive.

“This however would mean that tariffs would apply to export of UK agricultural goods to the EU.”

Which should be less of a concern, since the UK is a net importer of food. And if the EU were to apply tariffs on agricultural imports from the UK, the UK could apply tariffs on agricultural imports from the EU. The latter is of course what Norway does, and it’s one of the major motivations for staying out of the EU.

“The UK would lose any say over EU foreign policy”

Another reason to stay out of the EU, is the ability to have an independent foreign policy. EU countries increasingly often have to speak with one voice in international organisations like the UN and the WTO.

I think you need to explicate a bit further on your Norway/EEA comments re: foreign policy, as they are misleading. You imply that if we were part of the EEA, we would not have a say over EU foreign policy but would somehow be forced into it. Norway is NOT part of the Common Foreign & Security Policy, so it may have no say over it, but neither is it forced to implement and abide by it. Norway, as would the UK, can CHOOSE to align itself with whatever foreign policy the executive came up with in Brussels, but only if it wants to.

I think you are missing the point that there is one campaign out there which has political will behind it that just wants a referendum (the People’s Pledge), and one which is blatantly, right-wing, UKIP leaning and which focuses more on the out arguement – The EU Referendum Campaign. I would save your repudiating dismissal for the latter, as they have no arguments (or rather manipulated simplistic ones about being promised an In/Out referendum which actually the UK wasn’t – what we were promised was one on Lisbon) to back up their ‘claim to fame’ as it were. It’s clear to me that one is the traditional usual suspects focused solely on getting out of Europe and one is more focused on the advent of direct demoracy in the UK. Go after the right one eh?

The problem with your analysis is that it places too much focus on the Single Market element of the EU. Back when the UK joined, the Single Market was the only major element of the EU, but nowadays the EU is about far, far more than just a Single Market. The EU passes laws which affect pretty much every area of our lives, covering a scope at least as wide as Congress in the USA. You mention foreign policy as one example, which is, in itself, a huge area to expect the UK to cede control to the EU. But it goes far beyond foreign policy, the EU passes law on policing, immigration, the environment, transport, aid, health, criminal law, taxation, agriculture, education and many, many other areas. There are very few areas which are not impacted by EU law in some way and it is very likely that this trend will continue. The EU already resembles a federal superstate and in 30 years I suspect the process will be pretty much complete, with individual member states possessing very little sovereignty. Would you expect a ‘yes’ campaign to outline precisely the path that the EU is going to take?

The economic consequences of the UK leaving the EU are entirely unclear, in part because no-one knows precisely what would be negotiated on the UK’s exit. It is very likely that the UK would still be able to trade freely with the EU (both for the benefit of UK business and the EU as a whole) and in those circumstances the disruption caused could potentially be kept to a minimum. But, as outlined above, this argument is not just about economics.

We agree Scotland is a good comparison. As I said before, the SNP are bound to produce a set of proposals as to how independence would take place and what relationship Scotland would have to the rest of the UK. But these would only be proposals. If independence actually happened, then lengthy negotiations would ensue and no-one can say what the end result would be.

The major difference between Scottish independence and the UK leaving the EU is that in Scotland there is one coherent faction arguing for independence (the SNP) so it can put forward one clear set of proposals. If the UK were to have a referendum on leaving the EU then there is not one clear body which could put forward similar proposals. I’m sure UKIP would put out something, but then so would the Conservatives and so would the official ‘no’ campaign. This is the problem with your argument – to expect the ‘no’ campaign to be one uniform body which agrees precisely what a post-EU UK would look like. No-one knows for sure, but there are lots of different ideas held by various groups. The one thing those groups agree on is that the UK should leave the EU and this is what the referendum would be about, however imprecise the predictions as to the future are from both sides.

You say that the result of a ‘yes’ vote would be:

“…the relationship with the EU remains unchanged, and the UK fights its corner in the EU, winning some fights and losing some, just as it has since 1973.”

However, the EU has changed substantially since 1973, to the point that it is now unrecognisable from the entity that the UK joined. You are right to say that a ‘yes’ vote would mean that the UK would continue to win some fights and lose some fights, but what’s not clear is the direction that the EU will take and the degree to which the UK will be dragged along with the creation of what is, in effect, a federal superstate.

It is possible (though unlikely) that further efforts at integration will slow down and the EU will remain similar to what we have now. It is also possible that the EU will continue to integrate and national states will be increasingly sidelined in favour of the EU transnational bodies (Commission, Parliament, ECJ etc.) Although I cannot say with certainty, I suspect that many of the UK public would be ok with the first option, but would be against the second option.

If you demand certainty from the ‘no’ camp then you need to demand equal certainty from the ‘yes’ camp. Can you guarantee the direction that the EU will take over the next 30 years? I thought not.

This demonstrates the fallacy in your argument. A referendum can never give the public certainty as to what will happen given a certain result. The government of the day will implement the result of the referendum in the manner they believe is most advantageous to the national interest. If there was a ‘no’ vote then there would be some incredibly complicated negotiations to determine the relationship between the UK and the EU. In all likelihood it would be a very different model to those adopted by Norway and Switzerland, given the possible economic damage that the UK leaving would have on the EU.

Consider this as another illustration: the (likely) vote for Scottish independence in the next few years. No-one will be certain of how Scotland would become independent from England/Wales/NI and the relationship an independent Scotland would have with these nations. People will speculate, and I am sure that the SNP would put out some sort of proposal, but nothing would be certain until the result of the referendum and the ensuing negotiations. However, this does not mean that the Scottish people should be denied a vote – they will be voting on the principle of whether Scotland should become independent or not, with the precise details unknowable at that point in time.

Similarly, a vote on the UK’s continued membership of the EU would be a vote on principle, the precise implications of which can only be determined after the result.

@AJ – neat turn of phrase to avoid the question.

There are some areas of EU decision making – regarding foreign policy for example – where you might have a point. But the crucial issue are matters relating to the Single Market, and under what terms UK firms would be able to trade in that market. Some of the rules of that market are going to change over 10 years, 30 years etc., but the fundamentals of it have been the same for the past 30 years already.

You say the UK leaving the EU would have economic ‘damage’ for the EU. Yes, indeed. But the danger would be there would be far greater damage to the UK in terms of GDP percentages.

The Scotland issue is illustrative of how the debate on EU matters could go – the SNP has been pushed to explain how separation would work, in terms of trade, allocation of oil and gas wealth etc. The proposals might not be completely watertight but at least there are some, and the SNP would be forced to be more concrete. At the moment no-one who advocates UK withdrawal from the EU is anywhere near close enough to explaining how it would work.

Maybe the UK can join the US as an additional overseas state? Like this they would benefit from all the negotiation powers of the US vis-a-vis the EU.

Only downside: you would have to accept Obama (or who ever is next) replacing the Queen and you would pay things at the stores with a weaker and weaker Dollar.

I’m just very worried that if there were to be a referendum, the costs of non-EU for the UK would not be made clear. I hope this post, in its small way, might help to explain that.

Nice post. The UK has been facing the same catch-22 since the beginning: maintain independence and have the European project develop in an un-British direction, or sacrifice some sovereignty to undermine the project from the inside.

The Brits have largely forgotten the costs of the first option. They suffered first from being excluding from the Common Market, then they suffered after joining it because the CAP was skewed by the French to serve their own interests.

If the Brits had come in from the beginning, as by the bloc’s most prestigious and powerful member after WW2, it could have shaped it as it damn well pleased!

Today the British position is one of calculated schizophrenia and, I think, reasonably good for Britain, but perhaps not for Britain. A referendum I think would be good therapy against British denialism regarding the EU.

I’m not convinced the cultural-linguistic divide between the UK and the rest of Europe will get any smalelr though. I think it is growing. I’m not sure if the UK should/will ultimately stay in!