Jaroslaw Kaczynski, war dead, the EU and election dynamics

UPDATE 10.4.10: This is not a blog entry about the death of the Polish President Lech Kaczynski (Yahoo erroneously ranks this entry in searches for ‘Kaczynski dead’) – for news about that tragic accident please see this story from BBC News.

Former Polish PM Jaroslaw Kaczynski drew widespread scorn in Brussels in 2007 by stating that, when dealing with voting weights in the EU in the European Constitution / Treaty of Lisbon the number of men Poland lost in World War II ought to be taken into account. This from BBC News contains the background and some of the reactions. The EU, lest we forget, started out as a peace project to reconcile France and Germany after World War II so Kaczynski’s comments were rightly criticised.

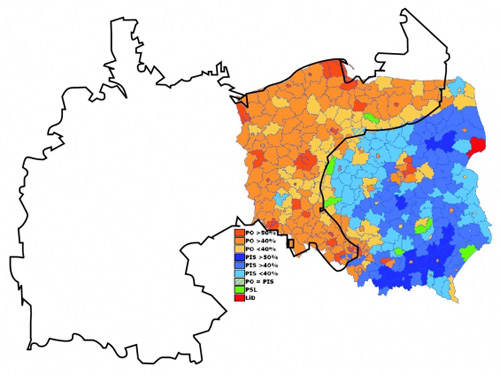

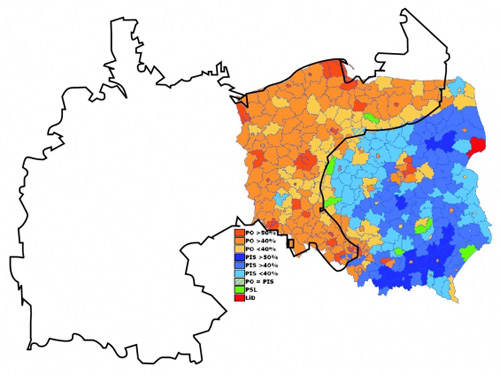

Fast forward 4 months and Kaczynski’s Law & Justice Party (PIS) was resoundingly defeated by Donald Tusk’s Civic Platform (PO) party in a general election. So how did Poland vote? This map shows the result – oranges are areas where PO was stronger than PIS, and blue areas are the inverse.

Only there’s an addition to the map: the black line shows the borders of Imperial Germany up until 1918. A quite remarkable fit. The map is from the excellent blog Strange Maps, and was produced by David G.D. Hecht. I first heard about it from Kosmopolit.

So is there something deeper behind the anti-Germanic rhetoric of Law & Justice?

**********************

First Observation: The map that you show also corresponds to Polish support for joining the European Union in the referendum in 2003. Take a look at the map here:

http://www.electoralgeography.com/new/en/wp-content/gallery/poland2003/2003-poland-referendum-european-union.gif

***********************

Second Observation: There is a map of unemployment in Poland (a key indicator of economic development) available here:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9a/11_2008_Bezrobocie_wg_powiatow_Barry_Kent.PNG/592px-11_2008_Bezrobocie_wg_powiatow_Barry_Kent.PNG

The unemployment statistics undermine the “economic argument,” since it’s clear that there is no clear economic division between Rural Western Poland versus Rural Eastern Poland (rather, each region has developed and impoverished districts). Nonetheless, the poor areas of Western Poland vote the same as the rich areas, and the same in Eastern Poland (poor urban areas vote the same as rich urban areas, and poor rural areas vote the same as more developed rural areas). So clearly, something else is drawing the political boundaries.

The strong connection between frequency of Church attendance and support for the PiS (blue) party in Poland, on the other hand, has been extensively documented; the areas in Southeastern Poland that are the bluest are also where Church attendance is the strongest. The single most-frequented Church district in Poland is Tarnow in the Southeast, while the least-frequented in Szczecin in the extreme northwest (which as you can see is bright orange). So I think I’m a fan of Mr. Egan’s theory. The regions of Poland that are the least conservative and most pro-European are also the regions where the historic influence of the Catholic Church is the weakest.

The reason you see the general trend in western versus eastern Poland has a simpler explanation than what has been so far offered. The areas of western Poland were under German/Prussian control and intensively developed. When Poland assumed control of its western territories, some of which were part of Poland at the time of WWII and the Partitions and some of which were lost by Poland centuries earlier, it also received a more developed land in terms of industry and infrastructure, but also proximity to western Europe and natural resources in Silesia and seacoast in Pomerania. As a result, the economy of western Poland is significantly stronger than in eastern Poland and dictates the political leanings of their respective populations.

Jon –

I only recently saw the map on the Polish election Wikipedia.

I was IMMEDIATELY hit by the comparison with the pre-1914 border.

On closer inspection there are additional elements to be gleaned.

First, the urban areas of Warsaw and Krakow are dark orange.

Lodz is also orange – thus urban areas in the east buck the PIS trend.

Second, although the eastern areas comprise Grand Ducky Poland under the Russian Empire, those blue areas also include Galicia which was in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In fact, some of the bluest areas are in the former Galicia.

Third, areas that were ethnically Polish in West Prussia and Posen/Poznan are as orange or more orange than areas that were formerly ethnic German before German populations were expelled.

The combination of these three factors points to a significant cultural factor that existed before 1914 and that was somehow reinforced after 1945. What could that factor be? I suggest that it is the relative position of the Catholic Church.

In Russian Poland and Austrian Galicia, the Catholic Church was the dominant religious institution – somewhat favored by the state in its conservative social role, but always holding the risk of nationalism. In the Kingdom of Prussia within the German Empire, Protestantism held sway. In fact, Bismarck’s “Kulturkampf” was aimed against the Catholic Church and banned religious teaching in public schools and Jesuit education. Thus, by 1914, areas west of the German/Russian imperial boundary had very little Catholic influence, while those to the east in both Russian and Austrian territory had strong Catholic influence.

Since interwar Poland only lasted twenty years and was riven by internal divisions, the Catholic influence on territories incorporated from imperial Germany into newly independent Poland may have been minimal. However, following World War II, all of the territory east of the Oder-Neisse line were incorporated into Poland and most of the German population expelled. The communist government of Poland was not as actively antireligious as the government of the Soviet Union, but it certainly did not favor the cultural role of the Catholic Church. Thus, the Catholic Church’s presence in those formerly German territories remained circumscribed – even though the population was no longer German. In fact, many Poles from eastern areas of Poland incorporated into Belorusia and Ukraine migrated to western Poland.

The political influence of PIS is not limited only to anti-German rhetoric. It also includes vehement opposition to abortion rights and gay rights – both of which reflect Catholic positions. When one looks at the urban enclaves in the eastern part of Poland that voted PO, it seems clear that the visible 1914 border demarcates the relative cultural influence of the Catholic Church.

Hello!

This map is extremely interesting. I didn’t know there was such an obvious overlap, although it’s widely known that the richer (Western) regions support the liberal party. Thanks for your post, Jon!

I think there is at least one moral: national borders are something not so permanent as some people wish them to be and national identities are much more mixed that we usually assume them to be, so why not to relax all this stuff a little in a broader space?