A framework for understanding online privacy

Privacy, and the need to protect it, is one of the most common calls of those who fear the rise and importance of social networks. It was the issue that was behind a panel I attended at World Economic Forum in Istanbul entitled “The Security-Privacy-Freedom Nexus”, with panellists dropping the word into their responses to the moderator’s questions. There’s even a blog post on the Forum Blog that touches on the subject.

Privacy, and the need to protect it, is one of the most common calls of those who fear the rise and importance of social networks. It was the issue that was behind a panel I attended at World Economic Forum in Istanbul entitled “The Security-Privacy-Freedom Nexus”, with panellists dropping the word into their responses to the moderator’s questions. There’s even a blog post on the Forum Blog that touches on the subject.

But what does privacy in an online context actually mean?

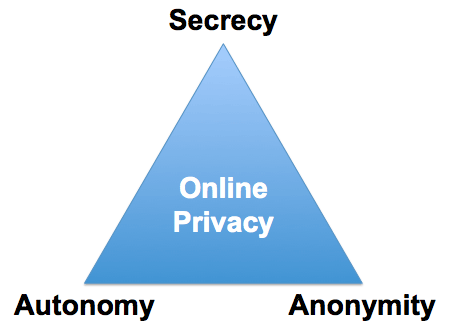

It’s a question I’ve grappled with for some time, and one that was clearly and elegantly explained by Eben Moglen in this keynote (it’s 40 mins long, but worth watching). Moglen sums up privacy as comprising three components, shown and slightly adapted here in the triangle:

- Secrecy is the ability for two people to communicate without others being party to their communications

- Anonymity is the ability to communicate without the source or the recipient being known

- Autonomy is the ability to control who knows what about you and holds data about you

Of course none of these are absolute, and – for more or less anything to function – we need to partially or completely give up some of these things at some times online. Facebook obliges us to ditch anonymity, and the principle critique of that network is that it gives us too little autonomy over its use of our data. This is also behind Reding’s “right to be forgotten“. The Chinese government is concerned enough about anonymity to mean its trying to oblige real names to be used on Weibo. The need to retain secrecy is the principal objection to UK internet surveillance proposals.

Before rejecting this framework (why – in liberal democracies – should we even need these three components of privacy?) think about the Arab Spring, and the need for citizens to overthrow a corrupt regime. Then think of Hungary or Azerbaijan. Or the UK government losing data about 25 million citizens. If we, in Western Europe, cannot respect these basics online, where does that leave us when trying to advocate the overthrow of dictators elsewhere? Or efforts to forbid European countries from exporting surveillance technology? It’s surely not right to say anonymous networking is OK for Tahrir but not for Tottenham.

At the limit, yes. But is that genuinely a free choice if 99% of your friends are using it?

“Facebook obliges us to ditch anonymity, and the principle critique of that network is that it gives us too little autonomy over its use of our data.”

Actually, FaceBook gives you total autonomy because (odd thought, this) you are absolutely free not to use it at all. That’s right—not have an account at all! Shock!

DK